Barn: drying-in and getting ready for framing inspection... It was a busy day around here today – not only was the driveway paved, but the builders had an extra large crew here today (5 or 6 people all day).

Two people were hard at work “drying-in” the roof – installing the underlayment that the steel roof will sit on top of. They finished about 80% of the roof today; the remainder will be done early tomorrow. Then they start on our house's roof.

Three (and occasionally, four) people were working inside the barn, framing the interior walls to be ready for the framing inspector tomorrow afternoon. There are several interior walls. They framed out the bathroom/boiler room, along with two partitions that go all the way across the barn, dividing it into three “rooms” (the garage, my workshop, and Debbie's dog agility arena). By the time they left this afternoon, all that framing was complete. Tomorrow they're going to start wrapping the barn in “house wrap” (Tyvek cloth) and installing windows and doors, to weather-proof the work done so far.

The photos, in time order:

Monday, October 13, 2014

Asphalt: done!

Asphalt: done! The paving crew was here for most of the day, about 7 hours all together. The last worker was the roller and thumper operator, who spent a couple of hours making the pavement perfectly, gloriously flat – and with the slight (desirable) tilt so that any water that hits the road will run off.

I found the whole process interesting to watch. As is often the case, there's far more to getting pavement in place than one might think. The first step was for the foreman to mark (with temporary spray paint) the patches for the paving machine to do. The trick to this is to make sure that every patch is wider than the machine's minimum width (about 8'), narrower than its maximum width (about 14'), and with an end point that is still unpaved. For a driveway that's very odd shaped, as ours is, this is quite a tricky feat! The paving machine automates much of the work of placing the asphalt in the right place, in the right thickness – but it's a fairly low level of automation, as the machine needs between 4 and 7 people to operate it. Then comes the rolling and thumping, which compacts the placed asphalt (about 20%, by eyeball) and makes the top nice and smooth. After watching for a while, I decided that the most skilled job there was the guy who ran the roller and thumper. Before he started his work, each patch was rough and soft. By the time he was done, it was hard and smooth. Occasionally he'd find a place where the wrong amount of asphalt had been placed, which was then quickly corrected – but it was the roller operator who did the finding. This fellow did a bang-up job on our driveway.

The photos below are in time order: work in progress, a few views of the finished result, and then the last three show my homemade signage at the entrance to our driveway from the main road. That signage greatly amused the paving crew :) – but they said it was a darned good idea, and hopefully might keep the UPS guy from messing up my nice new asphalt! We can drive cars on it tomorrow afternoon, but we have to be careful not to turn the wheels (steering) while motionless for a couple of weeks, until the surface has a chance to get good and hard...

I found the whole process interesting to watch. As is often the case, there's far more to getting pavement in place than one might think. The first step was for the foreman to mark (with temporary spray paint) the patches for the paving machine to do. The trick to this is to make sure that every patch is wider than the machine's minimum width (about 8'), narrower than its maximum width (about 14'), and with an end point that is still unpaved. For a driveway that's very odd shaped, as ours is, this is quite a tricky feat! The paving machine automates much of the work of placing the asphalt in the right place, in the right thickness – but it's a fairly low level of automation, as the machine needs between 4 and 7 people to operate it. Then comes the rolling and thumping, which compacts the placed asphalt (about 20%, by eyeball) and makes the top nice and smooth. After watching for a while, I decided that the most skilled job there was the guy who ran the roller and thumper. Before he started his work, each patch was rough and soft. By the time he was done, it was hard and smooth. Occasionally he'd find a place where the wrong amount of asphalt had been placed, which was then quickly corrected – but it was the roller operator who did the finding. This fellow did a bang-up job on our driveway.

The photos below are in time order: work in progress, a few views of the finished result, and then the last three show my homemade signage at the entrance to our driveway from the main road. That signage greatly amused the paving crew :) – but they said it was a darned good idea, and hopefully might keep the UPS guy from messing up my nice new asphalt! We can drive cars on it tomorrow afternoon, but we have to be careful not to turn the wheels (steering) while motionless for a couple of weeks, until the surface has a chance to get good and hard...

Quote of the day:

Quote of the day: the pithiest summation of the Obamanator yet:

Awesome, Mr. Reynolds. Just awesome...

“If a problem can’t be solved by blaming Republicans, Obama can’t solve it.”Glenn Reynolds, aka the InstaPundit. Source.

Awesome, Mr. Reynolds. Just awesome...

Asphalt: it begins!

Asphalt: it begins! The paving machine has arrived and has gone to work. Woo hoo! They're starting at the point where our driveway meets the road, and then working their way into our property...

Dr. Bretz and the Scablands of Washington state...

Dr. Bretz and the Scablands of Washington state... I first heard about this story on a trip with my dad, about twenty years ago. Today (and in '94) geologists generally agree that the “scablands” were formed by a series of massive floods from the prehistoric Lake Missoula that used to cover large chunks of Idaho and Montana, and parts of northeastern Washington and Canada. The lake was formed by a massive ice dam near the present-day Sandpoint, Idaho; the breakup of that ice dam caused the lake to drain, flooding a huge area downstream of it with almost unimaginably huge intermittent flows.

Scott Johnson has a piece in ars technica (with lots of photos) that discusses this in layman's terms, but in substantial detail. It's an excellent piece, and well worth a half-hour or so of your time to read it, and to see the photos of the area if you're unfamiliar with it.

We once owned some land not far from Sandpoint, and in our travels to the region became quite familiar with it. Parts of western Idaho (near Moscow) benefited from the flood that formed the scablands, as huge quantities of the scoured soil ended up there. This forms a large area of extraordinarily rich farmland today.

Reading this piece brought back a fond memory of that trip with my dad. We were driving through one of the coulees described in the article, and my dad was excitedly pointing out the evidence of the flood (a large notch with no stream today, and a bed of huge “ripples” – evidence that he had only read about before, not seen. As we drove, he told me the outlines of the story of Dr. Bretz's research, and in particular the resistance the geology world had to Dr. Bretz's notion that the scablands were formed by a catastrophic flood. My dad loved the way that Dr. Bretz slowly, persistently whittled away at all the objections to his theory – and eventually, after 40 years, lived to see his theory generally accepted. He also won the Penrose Medal (the most prestigious award in geology) in 1979. My dad loved this sort of story – the expert who proves to be right after years of the “experts” laughing at him. Geology, for some reason, is a rich source of such stories, and my dad knew quite a few of them. I think Dr. Bretz and his catastrophic flood was one of his favorites, though.

Oh, I miss him so...

Scott Johnson has a piece in ars technica (with lots of photos) that discusses this in layman's terms, but in substantial detail. It's an excellent piece, and well worth a half-hour or so of your time to read it, and to see the photos of the area if you're unfamiliar with it.

We once owned some land not far from Sandpoint, and in our travels to the region became quite familiar with it. Parts of western Idaho (near Moscow) benefited from the flood that formed the scablands, as huge quantities of the scoured soil ended up there. This forms a large area of extraordinarily rich farmland today.

Reading this piece brought back a fond memory of that trip with my dad. We were driving through one of the coulees described in the article, and my dad was excitedly pointing out the evidence of the flood (a large notch with no stream today, and a bed of huge “ripples” – evidence that he had only read about before, not seen. As we drove, he told me the outlines of the story of Dr. Bretz's research, and in particular the resistance the geology world had to Dr. Bretz's notion that the scablands were formed by a catastrophic flood. My dad loved the way that Dr. Bretz slowly, persistently whittled away at all the objections to his theory – and eventually, after 40 years, lived to see his theory generally accepted. He also won the Penrose Medal (the most prestigious award in geology) in 1979. My dad loved this sort of story – the expert who proves to be right after years of the “experts” laughing at him. Geology, for some reason, is a rich source of such stories, and my dad knew quite a few of them. I think Dr. Bretz and his catastrophic flood was one of his favorites, though.

Oh, I miss him so...

Sprite lightning...

“...requires continuous miracles interspersed with acts of God to be successful.”

“...requires continuous miracles interspersed with acts of God to be successful.” The subject is the space shuttle's controversial launch abort plan...

Explain this image!

Explain this image! This post does just that. I love the way he used simulations to figure it out...

As predicted by many, including me...

As predicted by many, including me ... the ObamaCare mandate is resulting in employers cutting work hours to under 30 hours per week, in order to avoid the ObamaCare mandate for employer-provided healthcare for full timer workers. During the debate over ObamaCare before it was enacted, the progressive establishment poo-pooed predictions that employers would behave this way, saying that other (generally unspecified) considerations would prevent them from doing so. It's therefore particularly amusing that one of the many employers pursuing the mandate-avoidance maneuver is the liberal bastion of the University of Colorado at Boulder...

Here we go again...

Here we go again... A group of three Italian researchers are claiming that they have verified the cold fusion reactor of a fourth Italian researcher. The verifiers' report is available online. The device they tested for 32 days produced 1.5 megawatt/hours of electrical power, with a very high energy density that cannot be explained (according to the verifiers) by any known chemical reaction. The verifiers – cautiously – speculate that cold fusion is the source of the power they observed. To me, the most striking result is the reported change in isotope mix during the test – if that's real, and not some artifact of measurement, then there had to be nuclear reactions occurring.

Needless to say, if this turns out to be for real, it will be a world-changing discovery. Our civilization's energy infrastructure would be completely upended. We'd all have fusion generators in our homes and cars, power lines and gas lines would go away, gas stations would go out of business – and that's just for starters!

Let the accusations of fraud, ad hominem attacks, and scientific detective work begin!

Needless to say, if this turns out to be for real, it will be a world-changing discovery. Our civilization's energy infrastructure would be completely upended. We'd all have fusion generators in our homes and cars, power lines and gas lines would go away, gas stations would go out of business – and that's just for starters!

Let the accusations of fraud, ad hominem attacks, and scientific detective work begin!

Dragon's blood trees...

Dragon's blood trees... From Socotra, Yemen, in 2010. Dracaena cinnabari, commonly known as dragon's blood tree (after the red resinous exudate from the tree's berries). The photo is a beautiful example of how monochromatic (black & white) photography can actually enhance an image...

Stick bug...

Stick bug... My mom (who lives near Charlottesville, Virginia) sent along this photo of a stick bug she spotted on her house (click to embiggen). What a monster! I remember these when I was a kid in New Jersey, but I haven't seen any in either California or Utah.

Their appearance is a defensive mechanism; it makes them hard for predators to spot. Stick bugs eat leaves, and mostly at night. During the day, they mostly stay still, the better to foil the predators that would like to eat them...

Their appearance is a defensive mechanism; it makes them hard for predators to spot. Stick bugs eat leaves, and mostly at night. During the day, they mostly stay still, the better to foil the predators that would like to eat them...

The end of civilization?

The end of civilization? You might think so from this quote:

“...has since reached a still more conspicuous peak of scientific infamy by inventing the aerophone – an instrument far more devastating in its effects and fraught with the destruction of human society.”Who is being taken to task here? And when? Thomas Edison, for his now-forgotten aerophone, in 1878. Panicking over technology advances is not a new thing :)

Fifty years of weather satellites...

Fifty years of weather satellites... When I was born, all weather observations were made by earthbound (or nearly so) instruments: on the land, at sea, or in the air. The maximum range of any observation was a few tens of miles, and at any given moment, only a tiny fraction of the earth's surface was being observed.

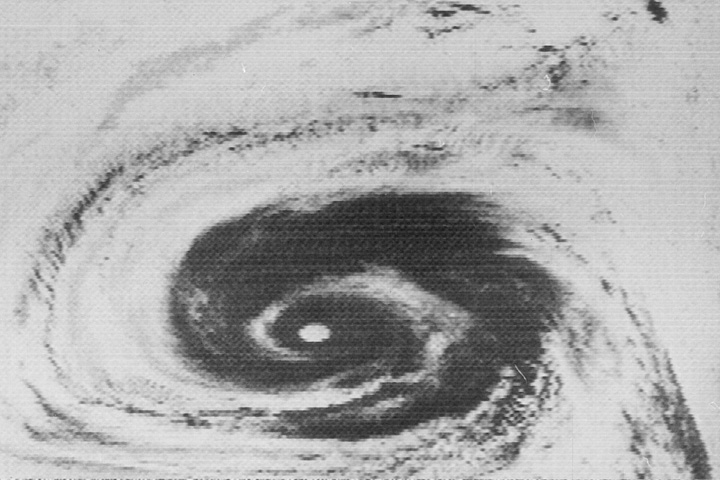

Just a couple of weeks before my twelfth birthday (just over 50 years ago), the U.S. launched Nimbus 1 and changed all that. Nimbus 1 was the first weather satellite with electronic image transmission capability, and over its lifetime it sent back thousands of images like the grainy hurricane photo above right. Its photos weren't the first satellite weather photos, but it was the first satellite that provided continuous coverage. At first it was most of the Earth's surface, then as more satellites were launched, it became 24 x 7 coverage of the entire Earth's surface.

It's hard to imagine, these days, just what a revolution that was. Prior to Nimbus, it was entirely normal for major weather events (like hurricanes, typhoons, or tropical storms) to strike by surprise, with little or no warning. The oceans and unpopulated land areas of earth are so vast that one of these things could easily form with no instruments around to see or track it. With the advent of Nimbus, such surprises suddenly were banished. A surprise hurricane simply couldn't happen today – all the eyes in the sky would see it long before it even reached hurricane status.

As with many things these days, once again I marvel at the advances in technology just over the course of my own life. When I was born, our ability to observe the Earth's weather was like someone trying to figure out New York City from a perch on top of the Empire State Building, able to observe only a few things while the sun is up. Today it's as though we have instruments on every street corner, seeing absolutely everything that's happening on every street, day and night.

The capabilities of the (now many) weather satellites are something we all take for granted. These days the satellites capture much more than images: they observe surface and atmospheric temperatures (at many elevations), winds, waves, atmospheric gases, polar ice, water levels, and much more. Satellites aren't the only weather-related technology marvels, either. Some other examples: the weather radars that cover much of the U.S. (and many other countries), the tens of thousands of amateur weather stations that are connected in vast realtime weather data networks, and the robotic underwater explorers that measure undersea salinity and temperature over vast stretches of our oceans. All of these, and much more, have been developed in just the past fifty years...

Just a couple of weeks before my twelfth birthday (just over 50 years ago), the U.S. launched Nimbus 1 and changed all that. Nimbus 1 was the first weather satellite with electronic image transmission capability, and over its lifetime it sent back thousands of images like the grainy hurricane photo above right. Its photos weren't the first satellite weather photos, but it was the first satellite that provided continuous coverage. At first it was most of the Earth's surface, then as more satellites were launched, it became 24 x 7 coverage of the entire Earth's surface.

It's hard to imagine, these days, just what a revolution that was. Prior to Nimbus, it was entirely normal for major weather events (like hurricanes, typhoons, or tropical storms) to strike by surprise, with little or no warning. The oceans and unpopulated land areas of earth are so vast that one of these things could easily form with no instruments around to see or track it. With the advent of Nimbus, such surprises suddenly were banished. A surprise hurricane simply couldn't happen today – all the eyes in the sky would see it long before it even reached hurricane status.

As with many things these days, once again I marvel at the advances in technology just over the course of my own life. When I was born, our ability to observe the Earth's weather was like someone trying to figure out New York City from a perch on top of the Empire State Building, able to observe only a few things while the sun is up. Today it's as though we have instruments on every street corner, seeing absolutely everything that's happening on every street, day and night.

The capabilities of the (now many) weather satellites are something we all take for granted. These days the satellites capture much more than images: they observe surface and atmospheric temperatures (at many elevations), winds, waves, atmospheric gases, polar ice, water levels, and much more. Satellites aren't the only weather-related technology marvels, either. Some other examples: the weather radars that cover much of the U.S. (and many other countries), the tens of thousands of amateur weather stations that are connected in vast realtime weather data networks, and the robotic underwater explorers that measure undersea salinity and temperature over vast stretches of our oceans. All of these, and much more, have been developed in just the past fifty years...

Sensuous, tempting chocolate!

I still have water!

I still have water! The water leak I (finally!) fixed yesterday is still banished; the fix is still holding. Hooray!

I didn't think I was the first person to ever make such a repair :) – but I didn't expect it was a common occurrence. Last night while I slept, two readers of this blog (Celeste S. and Sam W.) wrote to say they'd had similar experiences. Celeste and her husband even had the same “pop” and geyser experience!

Two readers may not sound like a lot, but that's a surprisingly high percentage of the total number of my blog's readers :)

I didn't think I was the first person to ever make such a repair :) – but I didn't expect it was a common occurrence. Last night while I slept, two readers of this blog (Celeste S. and Sam W.) wrote to say they'd had similar experiences. Celeste and her husband even had the same “pop” and geyser experience!

Two readers may not sound like a lot, but that's a surprisingly high percentage of the total number of my blog's readers :)