Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good flight!

First unmanned flight of an F-16...

Geek: Why do array indices start at 0, and not 1?

Geek: Why do array indices start at 0, and not 1? I thought I knew why (the pointer arithmetic), but I was wrong. Mike Hoye did the research, and the result is a fun (though geekly) read...

Mexico is what happens...

Mexico is what happens... when the public sector unions get too powerful...

And I thought Amazon's drones were cool!

Words fail me...

Words fail me... But not Amazon's reviewers! The product at right is called the 2-in-1 iPotty with Activity Seat for iPad. When I first saw it, I thought it had to be a joke – but then I searched for the product on the Amazon site and it was actually there! As usual with a wacky product on Amazon, the reviews are the best part. Here's one of the 92 reviews posted when I wrote this:

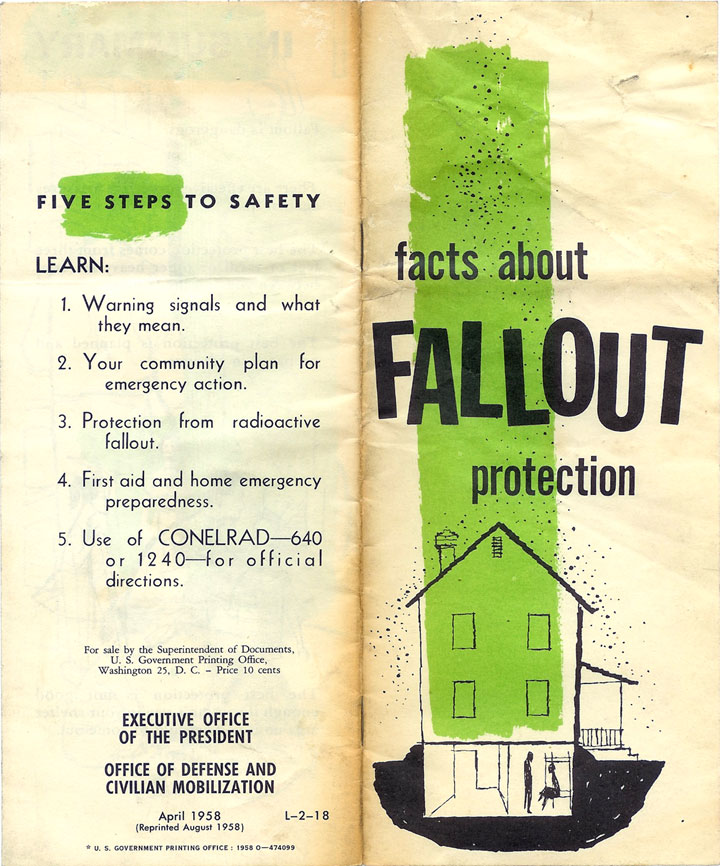

I remember this booklet!

I remember this booklet! It was sitting on my dad's desk, down in our basement. It's funny how your brain can dredge up details about a long-ago event, given the tiniest of nudges from a photo, a smell, or a sound. In this case, I remember not only the booklet itself, but also the ballpoint pen that lay next to it: black with a silver metal parts (the tip, the button, the clip, and a ring around the middle), some silver printing on it (an ad of some kind), and a distinctive and peculiar odor. This must have been around 1960 or so. I wonder why my brain thought that particular little piece of data needed to be filed away?

Seventeen photos of beautiful places on Earth...

Seventeen photos of beautiful places on Earth... like the French lavender field at right...

Shards...

Shards... I know Bill Whittle almost exclusively as a conservative commentator, especially for his excellent series of short videos. Today I ran across a long post of his titled Shards, wherein he talks about his relatively recent discovery of the Lord of the Rings trilogy (and other Tolkien works), and why he loves them so much. It's a fascinating piece, and I knew I was going to enjoy it when I read this bit near the beginning:

But twelve years ago, I saw The Fellowship of the Ring – somewhat reluctantly, I might add – and I loved it. I’ve read the Trilogy several times since then; read the astonishingly beautiful Silmarillion… I’ve read everything. And I now believe that J.R.R.Tolkien has created the single greatest work of literature in the history of the world. Because underneath the magic and the Elves and the Wizards is an endless allegory of good and evil; of sin and redemption; of hubris and arrogance and acts of transcendental courage in the face of certain death.If you, like me, are a Tolkien fan, you'll love Shards. If you're not a Tolkien fan, then just maybe this piece will nudge you to give his works a try...

These themes are so timeless, so universal and so powerful, and ultimately so spiritually satisfying because what Tolkien is selling – all that he’s selling, when it’s all said and done – are the cardinal virtues; courage, and faith, and more than anything: hope.

Not hope and change. Hope in the face of change. Hope for the eternal in the face of catastrophic change. Hope where there is no hope. And speaking for myself here, that is a message I need to hear in these dark days. So walk with me a little, because I have to tell this story in order to tell the one I need to tell.

TSA agent confiscates tiny toy pistol...

TSA agent confiscates tiny toy pistol... from a sock-puppet monkey. Because, you know, terrorists might really use little pistols with bullets the size of a rice grain to hijack a plane.

One thought came immediately to mind as I read and absorbed this story: the terrorists have won. They have succeeded in convincing Americans to let themselves be ruled by idiots...

One thought came immediately to mind as I read and absorbed this story: the terrorists have won. They have succeeded in convincing Americans to let themselves be ruled by idiots...

The trap of merit...

The trap of merit... Mickey Kaus may just be my favorite liberal. He's got a great piece up called The Great MacGuffin, about Obama's recent “Inequality” speech. The whole thing is good, but this part especially resonated with me:

3. The Trap of Merit: Obama draws a link between inequality and lack of mobility:

[W]hile we don’t promise equal outcomes, we have strived to deliver equal opportunity — the idea that success doesn’t depend on being born into wealth or privilege, it depends on effort and merit. …

In fact, we’ve often accepted more income inequality than many other nations for one big reason–because we were convinced that America is a place where even if youre born with nothing, with a little hard work you can improve your own situation over time and build something better to leave your kids. As Lincoln once said, “While we do not propose any war upon capital, we do wish to allow the humblest man an equal chance to get rich with everybody else.”

The problem is that alongside increased inequality, we’ve seen diminished levels of upward mobility in recent years. A child born in the top 20 percent has about a 2-in-3 chance of staying at or near the top. A child born into the bottom 20 percent has a less than 1-in-20 shot at making it to the top.

The argument is that as inequality grows it becomes harder to climb the ladder because the rungs are further apart. The problem, for this argument, is that declining mobility is also what you would expect if the meritocracy were working perfectly, without race or class prejudice (and inequality were stable or even shrinking). In a meritocracy, after all, the best rise to the top, the least talented and industrious wind up at the bottom. At some point, after a number of decades, maybe most of the talented will be at the top and the untalented at the bottom! Or at least, once the meritocratic centrifuge has sorted everyone out, there won’t be that many talented people at the bottom to rise in heartening success stories (and those stories that do turn up will mainly involve immigrants). Worse, if you grant that a reasonable share of “merit” is inherited, then you are going to wind up with a more static class structure for generation after generation. This is the scenario outlined by Harvard psychologist Richard Herrnstein. Just because it’s profoundly depressing doesn’t mean it’s not true. Yes, luck still plays a big role. No, genes aren’t everything, or even maybe a majority of everything. But they’re something, and we should think about Herrnstein before we whine that people aren’t rising to or falling from the top as much as they used to.

Pater: floating island...

Pater: floating island... At right, my dad is inspecting (with some amusement!) a giant wind vane. The arrowhead is made from an old automobile hood. We were in Humbug Valley, in the National Forest near Mt. Lassen National Park, in June 2007. We later heard from the wife of the guy who made this thing; she said it really did work...

Floating island...

Way back before most of my readers were born, my grandfather (my mom's father) owned a “camp” on the shore of Long Pond, near North Lincoln, Maine. It wasn't quite a house, but it was a big step up from camping. It had one large room with an open-beam ceiling, a little attached bedroom, a mostly-watertight roof, a screened-in porch facing the lake, a sink, and a wood stove – and most vitally, a big octagonal table where we could play cards (this, along with drinking beer and fishing, being the primary occupation of the adults who weren't my dad). The porch was set back about 25' from the lake's shore, and it had a steep staircase that let you walk down, over a boardwalk, and right onto a dock that floated perhaps 20' into the lake. The smells of fish and beer were always present.

When we first started visiting the camp, the only “facility” there was an old-fashioned outhouse 50' or so inland from the camp. Instead of toilet paper we had pages from some dodgy “detective” magazines that my grandfather liked to read, most of them featuring lurid cartoons of buxom, scantily-clad damsels in desperate need of being rescued. Later some additions were made to the cabin, including a tiny little bathroom scabbed onto the back side.

We spent part of most summers there when I was younger, often several weeks at a stretch. It was the kind of vacation that kids dream about – we had a canoe and a motorboat (with something like an 8 HP motor) at our disposal. We could swim whenever we wanted to. The weather was balmy and clear almost every day. There were fascinating and exotic “Maniac” (native residents of Maine) characters who were constantly stopping by for a chat, a beer, or a card game. There were loons on the lake, and sometimes we could watch them through the mist on the water in the mornings – and of course every night we'd hear their strange and wonderful cries.

And there was the floating island.

I've since discovered that floating islands are actually quite common, especially in certain parts of the world. Minnesota and Wisconsin for example, with climates similar to Maine's, have a particularly rich collection of them. But at the times I write of – late '50s and early '60s – I thought the floating island of Long Pond was something unique and nearly magical.

To get there required a long, slow motorboat trip from our camp, itself a grand adventure when we first made it (at quite a young age – I'm guessing 7 or 8 years old – for me). The embedded map at right shows what I believe is the floating island, the one that I'm writing about. Our camp was almost due west of it, about a mile away, on a stretch of Long Pond's shore that faces NNE.

Somehow my dad knew of the floating island's existence. It's exactly the sort of thing he'd be interested in seeing, for floating islands like that one are made up entirely of buoyant plants – and anything involving plants my dad would like :)

The first time I visited the floating island (I believe with my brother Scott and my sister Holly), my dad had already been there – so he knew exactly where it was, and what to expect when we got there. He tried to describe it to us, but my mental picture of it (based on his description) didn't match the reality at all. I was imagining an island that looked like other islands, with dirt and rocks, trees and shrubs, and maybe a cabin or two. That's not what it was like at all, as we discovered when my dad pulled our little motorboat up alongside it.

The first challenge my dad had was finding something secure to tie the boat to. Virtually everything on the floating island was just an inch or two above the water's surface – the tops of aquatic plants whose roots dangled in the water below and actually supplied the buoyancy that kept the island afloat. Occasionally, though, there were spots on the island where ordinary plants had somehow managed to eke out an existence – a few stunted shrubs showed up here and there. So he had to find a way to get the boat close enough to a shrub so that we could tie it up. We certainly wouldn't want the boat drifting away as we were walking around on that island!

He finally did find a secure mooring for us, and we got out to walk around. What an adventure that was! Even as little kids we weighed enough to make the island sink beneath us. The only reason we could walk around is that the roots of all these plants were thoroughly entangled with each other, making a sort of fabric of the entire island. Right where we were stepping we might sink down six inches or more, but the rest of the island, acting like a piece of stretchy fabric, would keep us from going further. However, once in a while one of us (especially my then much heavier dad) would tear the fabric of the island and one foot would suddenly drop toward the bottom of the lake! I don't remember any of us actually punching through completely, so that fabric must have generally been pretty strong.

My dad was fascinated by the assortment of non-aquatic plants that had managed to survive on the floating island. With basically no soil at all, it was a strange place to find things that ordinarily grew on land. We were all fascinated by the carnivorous aquatic plants (pitcher plants) that grew there – what kid wouldn't love a plant that trapped and ate bugs? As we walked about there, we were completely surrounded by the unusual. Along with the odd plants and strange footing, there were holes in the island through which we could see down into the lake. Occasionally a fish would come up through those holes to catch a bug, sometimes with a satisfyingly large splash. There were chipmunks living on the island; apparently something grew there that they could eat. When another boat passed by, it's wake would cause the entire island to wiggle up and down. In a few places we spotted buoyant flotsam that had been incorporated into the fabric of the island – floats, pieces of lumber, driftwood, pine cones, and even a few beer bottles. I loved that place, and visited it perhaps a half dozen times in later years. I never saw another person there.

Before letting us off the boat to walk on the floating island, my dad told us kids what to do if we should find ourselves in the water – basically, grab onto the island and yell. I remember his face as he was telling us this – he was uncharacteristically serious, and this surprised me, as (to me) it didn't seem like any more dangerous an adventure than any of a bazillion others I'd been on with my dad. My not-necessarily-logical thought process went basically like this: I'm with my dad, so what could go wrong? My dad was a bit more cautious, though in the end, nothing untoward actually happened.

But thinking back on it now, I can easily imagine why he'd have been worried. At the time, the floating island was a long way from any civilization (though the area around it has since been developed). There was nobody around who could help him if something went wrong. There were no cell phones on which he could call for help. The closest telephones were probably a half-hour's boat trip away. In that kind of isolation, he took three little kids out for a jaunt on an island that any one of us could have punched right through. It's the kind of calculated risk that I suspect even back then relatively few parents would have taken, and today, of course, that number would be even smaller.

When I think of all the adventures we had with my dad – many of which involved some (usually quite small) element of risk – I'm overwhelmed with gratitude to him for making those choices. My life is so much richer, with so many more now-cherished experiences and memories, because he judged the value of the experience greater than the risk.

Just once, on our 2005 trip to the San Juan Mountains, I brought this subject up in our conversation. We had just come back to our rental cabin after eating a meal at a restaurant in Ouray, and on the way home we'd seen a family bicycling – all wearing the politically-correct helmets, but riding right in the middle of a busy street. This amused my dad to no end, and he launched into an imaginative speculation about the degree to which the human gene pool would be improved if someone were to squash that family in the street. It seemed like a good moment, so I asked him, then, if he was conscious of balancing the value of an experience against the risk, especially when we were little kids.

It took him a while to cough up the answer, which was something like this: no, he wasn't really conscious of it, because in his mind there never were any noteworthy risks we were taking. If we fell off a cliff, sank under the floating island, or were stomped by an angry moose, then those were either just plain bad luck (which could happen at any time to anybody, no matter how cautious you were) or the result of us doing something stupid (in which case the species' gene pool might well be improved by our removal from it). In no case, he believed, were such concerns a reason to avoid an adventure or experience. He was not an advocate of reckless behavior – far from it, actually – but he also thought a that lot of behavior (like dangling your legs off a cliff top) was misjudged as reckless by the timid and stupid amongst us.

That's an uncommonly rational view of risk. I didn't recognize it as such until I was an adult myself, but that's exactly what it was. My dad's rational view of risk, combined with his love of experience and adventure, enriched my childhood beyond measure. They also had a huge impact on my developing personality and character as a young man. There have been many, many times when I've asked myself “What would my dad do?” – or, more often, “What decision would my dad most respect?”

My dad is gone now, and I won't be able to share any more adventures with him. But I have the memories of many adventures we did share, and his guiding voice still lives within me...

Labels:

Pater

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)