Hip hip hooray!

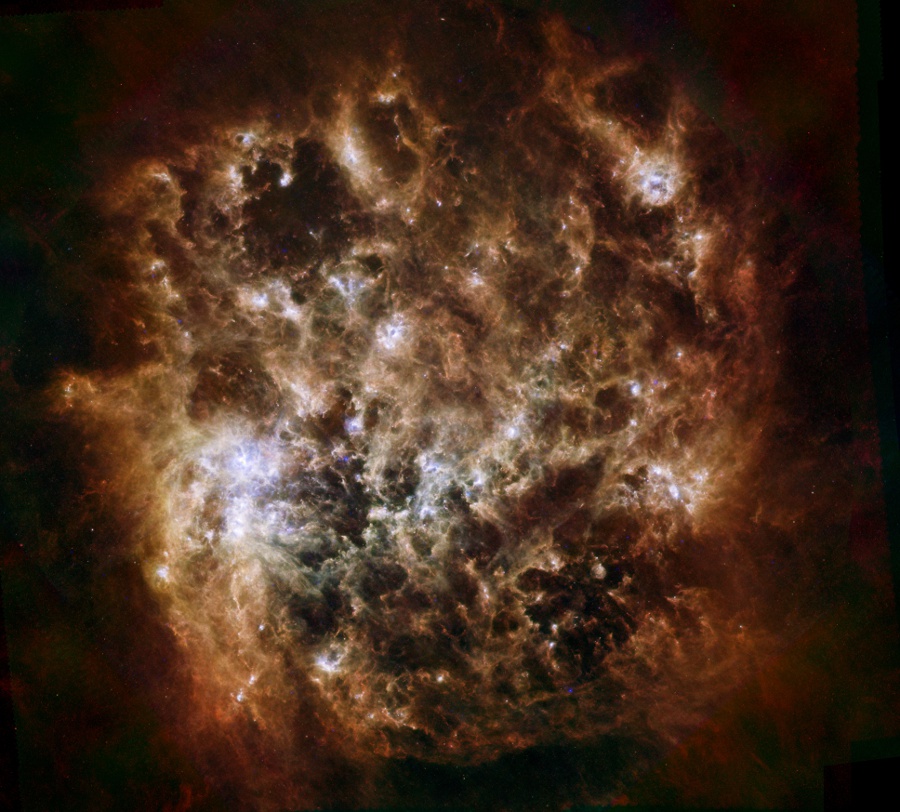

Curiosity has been offline for several weeks, after a software glitch (and possibly a memory failure; reports vary). The photo at right was returned amongst the first new batch since the glitch first occurred. It's very nice to see that! In just over a week, Curiosity (and all of Mars) will be on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth, so for a few weeks after that it will be “radio silence” for all the robotic explorers orbiting and sitting on the surface of Mars. Let's hope they all wake back up successfully when Mars is out of occlusion!

Saturday, March 23, 2013

We Aren't the World...

Experiments in psychology and sociology are plagued by uncontrolled (and perhaps uncontrollable) variables and difficulties in replication. For any engineer or scientist used to the somewhat firmer ground of the “hard” sciences, this makes investigations into human behavior seem like something other than science and closer to opinion. It doesn't help that facets of these softer sciences that are believed to be true are routinely and frequently overturned.

On that theme, here's an article exploring one of the more recent such overturnings. My main reactions after reading this: (1) don't believe anything is actually “known” in those fields, and (2) I'm sure glad my own areas of interest aren't quite so ambiguous and difficult to measure – my oscilloscope and voltmeter work every time, with perfectly repeatable results :)

On that theme, here's an article exploring one of the more recent such overturnings. My main reactions after reading this: (1) don't believe anything is actually “known” in those fields, and (2) I'm sure glad my own areas of interest aren't quite so ambiguous and difficult to measure – my oscilloscope and voltmeter work every time, with perfectly repeatable results :)

Labels:

Psychology,

Science,

Sociology

Picking CPU Registers...

On many CPU architectures, especially older ones, there are a relatively small number (sometimes only two or three!) of CPU registers. Modern CPUs are sometimes much more symmetric with respect to register set architecture. If you're an assembly language programmer, you know all about registers. If you're not, you can think of them as particularly fast memory locations that machine-level computer instructions can access directly (that is, without having a memory address).

This characteristic of a small number of registers wasn't limited to microprocessors; all the early “mainframe” and “mini” computers were built the same way. The first mainframe computer I worked with was a Univac CP-642A, and if I remember correctly it had just four registers: A, Q, I, and the program counter. All of the subsequent mainframes and minis I worked with were also machines with limited register sets, with some of the most modern of them having a couple dozen registers. Similarly, all the early single-chip microcomputers I worked with had very limited register sets as well. The TI 99000 attempted to move a lot of register functionality into memory locations, but even it had over a dozen specialized registers.

All of these machines with limited register sets shared another characteristic: to various degrees the registers were specialized. One register might have special capabilities for increment and decrement. Another might be specially usable as an index into memory. Another might be part of double-precision multiply and divide operands. Or perhaps a couple of registers might have a special “swap” capability. This sort of thing was quite normal in those early CPUs, and the special register set capabilities were directly reflected in the machine-level instruction sets.

William Swanson has a nice article up exploring the Intel 8086 register set architecture in quite a bit of detail. It's a specific case of this more general design characteristic. Reading this brought back a lot of memories, both from the distant past :) and more recently, with PIC single-chip systems...

This characteristic of a small number of registers wasn't limited to microprocessors; all the early “mainframe” and “mini” computers were built the same way. The first mainframe computer I worked with was a Univac CP-642A, and if I remember correctly it had just four registers: A, Q, I, and the program counter. All of the subsequent mainframes and minis I worked with were also machines with limited register sets, with some of the most modern of them having a couple dozen registers. Similarly, all the early single-chip microcomputers I worked with had very limited register sets as well. The TI 99000 attempted to move a lot of register functionality into memory locations, but even it had over a dozen specialized registers.

All of these machines with limited register sets shared another characteristic: to various degrees the registers were specialized. One register might have special capabilities for increment and decrement. Another might be specially usable as an index into memory. Another might be part of double-precision multiply and divide operands. Or perhaps a couple of registers might have a special “swap” capability. This sort of thing was quite normal in those early CPUs, and the special register set capabilities were directly reflected in the machine-level instruction sets.

William Swanson has a nice article up exploring the Intel 8086 register set architecture in quite a bit of detail. It's a specific case of this more general design characteristic. Reading this brought back a lot of memories, both from the distant past :) and more recently, with PIC single-chip systems...

Labels:

Computer,

Geek,

History,

Technology

Massive Construction Underneath New York...

The Atlantic has a great article up about the massive construction project currently underway, mainly deep underground in New York City. It's been going on for over five years already, and it's truly enormous in scale – yet most people have never heard about it, and most New York residents have never seen any evidence of it.

Being a government project, of course it's massively over-budget and behind schedule. It would be fabulously shocking if not :)

I'm not a fan of big cities in general, and New York is amongst my least favorite. But the sheer scale of this civil engineering project leaves even me with my jaw dropped. Lots more photos at the link; the one below is a custom (and massive!) tunnel-boring machine built for the project.

Being a government project, of course it's massively over-budget and behind schedule. It would be fabulously shocking if not :)

I'm not a fan of big cities in general, and New York is amongst my least favorite. But the sheer scale of this civil engineering project leaves even me with my jaw dropped. Lots more photos at the link; the one below is a custom (and massive!) tunnel-boring machine built for the project.

Labels:

Awesome,

Civil Engineering,

New York

Unfit for Work...

NPR has an article posted digging into the phenomenon of skyrocketing employment disability rates in the U.S. There are lots of interesting nuggets in the article, like the infographic below showing how the kinds of disabilities being claimed have changed over 50 years. Read the facts, and come to your own conclusions about the causes. Remember that the source is NPR: sources are likely filtered, and opinions carefully vetted to fit the progressive world view. I'll offer one additional caution: most of the things being measured are not well-isolated metrics. For example, the infographic below is almost certainly colored by the progress of medicine in that same period - so, for instance, the lower rate of claims for respiratory diseases is probably caused (at least partly) by advances in respiratory medicine, and not at all by behavioral changes...

Labels:

Disability,

Policy,

Politics

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)